![Don’t Panic: The comprehensive Ars Technica guide to the coronavirus [Updated 4/4]](https://cdn.arstechnica.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/covid19-explainer-starfield-800x450.jpg)

Nearly 1.2 million people have been infected with a new coronavirus that has spread widely from its origin in China over the past few months. Nearly 64,000 have already died. Our comprehensive guide for understanding and navigating this global public health threat is below.

This is a rapidly developing epidemic, and we will update this guide periodically to keep you as prepared and informed as possible.

March 8: Initial publication of the document.

Latest Updates 4/4/2020: Updates have been added to the sections on deaths, how transmission compares with flu, and masks. The global and US case counts have also been updated.

A list of all updates and additions to this document can be found at the end.

Table of Contents

- How worried should I be?

- What is SARS-CoV-2?

- Where did SARS-CoV-2 come from?

- How did it start infecting people?

- What happens when you’re infected with SARS-CoV-2?

- What are the symptoms?

- Does COVID-19 cause a lost sense of smell? [New, 3/23/2020]

- How severe is the infection?

- Who is most at risk of getting critically ill and dying?

- Are men more at risk?

- Are children less at risk? [Updated 3/20/2020]

- Are pregnant women at high risk? [New, 3/19/2020]

- US data on risk for millennials [New, 3/20/2020]

- How long does COVID-19 last?

- ⇒ How many people die from the infection? [UPDATED 4/4/2020]

- How does COVID-19 compare with seasonal flu in terms of symptoms and deaths?

- How does SARS-CoV-2 spread? [Updated 3/12/2020]

- ⇒ How does coronavirus transmission compare with flu? [UPDATE 3/13/2020, 4/4/2020]

- How contagious is it? [New, 3/9/2020]

- Can I get SARS-CoV-2 from my pet? Can I give it to my pet? [New, 3/9/2020]

- If I get COVID-19, will I then be immune, or could I get re-infected? [Updated, 3/20/2020]

- How likely am I to get it in normal life?

- What can I do to prevent spread and protect myself?

- Should I get a flu vaccine?

- ⇒ When, if ever, should I buy or use a face mask? [UPDATE, 4/4/2020]

- Should I avoid large gatherings and travel? [Updated 3/13/2020]

- What precautions should I take if I do travel?

- Do quarantines, isolations, and social-distancing measures work to contain the virus? [New, 3/10/2020]

- How should I prepare for the worst-case scenario?

- Should I keep anything in my medicine cabinet for COVID-19? [Updated, 3/16/2020]

- Can X home remedy or product prevent, treat, or cure COVID-19? [New, 3/11/2020]

- Should I go to a doctor if I think I have COVID-19?

- When should I seek emergency care?

- Is the US healthcare system ready for this?

- What are the problems with testing in the US?

- ⇒ Current cases in the US [Updated, 4/4/2020]

- What could happen if healthcare facilities become overwhelmed?

- When will all of this be over in the US?

- Will SARS-CoV-2 die down in the summer?

- Will it become a seasonal infection?

- What about treatments and vaccines?

- A list of all updates and additions

How worried should I be?

You should be concerned and take this seriously. But you should not panic.

This is the mantra public health experts have adopted since the epidemic mushroomed in January—and it’s about as comforting as it is easy to accomplish. But it’s important that we all try.

This new coronavirus—dubbed SARS-CoV-2—is unquestionably dangerous. It causes a disease called COVID-19, which can be deadly, particularly for older people and those with underlying health conditions. While the death rate among infected people is unclear, even some current low estimates are seven-fold higher than the estimate for seasonal influenza.

And SARS-CoV-2 is here in the US, and it's circulating—we are only starting to determine where it is and how far it has spread. Problems with federal testing have delayed our ability to detect infections in travelers. And as we work to catch up, the virus has kept moving. It now appears to be spreading in several communities across the country. It’s unclear if we will be able to get ahead of it and contain it; even if we can, it will take a lot of resources and effort to do it.

All that said, SARS-CoV-2 is not an existential threat. While it can be deadly, around 80 percent of cases are mild to moderate, and people recover within a week or two. Moreover, there are obvious, evidence-based actions we can take to protect ourselves, our loved ones, and our communities overall.

Now is not the time for panic, which will only get in the way of what you need to be doing. While it’s completely understandable to be worried, your best bet to getting through this unscathed is to channel that anxious energy into doing what you can to stop SARS-COV-2 from spreading.

And to do that, you first need to have the most complete, accurate information on the situation as you can. To that end, below is our best attempt to address all of the questions you might have about SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19, and the situation in the US.

We’ll start with where all of this starts—the virus itself.

What is SARS-CoV-2?

SARS-CoV-2 stands for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2. As the name suggests, it’s a coronavirus and is related to the coronavirus that causes SARS (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome). Note: When SARS-CoV-2 was first identified it was provisionally dubbed 2019 novel coronavirus, or 2019-nCoV.

Coronaviruses are a large family of viruses that get their name from the halo of spiked proteins that adorn their outer surface, which resemble a crown (corona) under a microscope. As a family, they infect a wide range of animals, including humans.

With the discovery of SARS-CoV-2, there are now seven types of coronaviruses known to infect humans. Four regularly circulate in humans and mostly cause mild to moderate upper-respiratory tract infections—common colds, essentially.

The other three are coronaviruses that recently jumped from animal hosts to humans, resulting in more severe disease. These include SARS-CoV-2 as well as MERS-CoV, which causes Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS), and SARS-CoV, which causes SARS.

In all three of these cases, the viruses are thought to have moved from bats—which have a large number of coronavirus strains circulating—to humans via an intermediate animal host. Researchers have linked SARS-CoV to viruses in bats, which may have moved to humans through masked palm civets and raccoon dogs sold for food in live-animal street markets in China. MERS is thought to have spread from bats to dromedary camels before jumping to humans.

Where did SARS-CoV-2 come from?

SARS-CoV-2 is related to coronaviruses in bats, but its intermediate animal host and route to humans are not yet clear. There has been plenty of speculation that the intermediate host could be pangolins, but that is not confirmed.

How did it start infecting people?

While the identity of SARS-CoV-2’s intermediate host remains unknown, researchers suspect the mystery animal was present in a live animal market in Wuhan, China—the capital city of China’s central Hubei Province and the epicenter of the outbreak. The market, which was later described in Chinese state media reports as “filthy and messy,” sold a wide range of seafood and live animals, some wild. Many of the initial SARS-CoV-2 infections were linked to the market; in fact, many early cases were in people who worked there.

Public health experts suspect that the untidiness of the market could have led to the virus’ spread. Such markets are notorious for helping to launch new infectious diseases—they tend to cram humans together with a variety of live animals that have their own menageries of pathogens. Close quarters, meat preparation, and poor hygienic conditions all offer viruses an inordinate number of opportunities to recombine, mutate, and leap to new hosts, including humans

That said, a report in The Lancet describing 41 early cases in the outbreak indicates that the earliest identified person sickened with SARS-CoV-2 had no links to the market. As Ars has reported before, the case was in a man whose infection began causing symptoms on December 1, 2019. None of the man’s family became ill, and he had no ties to any of the other cases in the outbreak.

The significance of this and the ultimate source of the outbreak remain unknown.

The market was shut down and sanitized by Chinese officials on January 1 as the outbreak began to pick up.

What happens when you’re infected with SARS-CoV-2?

In people, SARS-CoV-2 causes a disease dubbed COVID-19 by the World Health Organization (WHO). As the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) points out, the ‘CO’ stands for ‘corona,’ ‘VI’ for ‘virus,’ and ‘D’ for disease.

What are the symptoms?

COVID-19 is a disease with a range of symptoms and severities, and we are still learning about the full spectrum. So far, it seems to span from mild or potentially asymptomatic cases all the way to moderate pneumonia, severe pneumonia, respiratory distress, organ failure and, for some, death.

Many cases start out with fever, fatigue and mild respiratory symptoms, like a dry cough. Most cases don’t get much worse, but some do progress into a serious illness.

According to data from nearly 56,000 laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 patients in China, the rundown of common symptoms went as follows:

- 88 percent had a fever

- 68 percent had a dry cough

- 38 percent had fatigue

- 33 percent coughed up phlegm

- 19 percent had shortness of breath

- 15 percent had joint or muscle pain

- 14 percent had a sore throat

- 14 percent headache

- 11 percent had chills

- 5 percent had nausea or vomiting

- 5 percent had nasal congestion

- 4 percent had diarrhea

- Less than one percent coughed up blood or blood-stained mucus

- Less than one percent had watery eyes

That data was published in a report by a band of international health experts assembled by the WHO and Chinese officials (called the WHO-China Joint mission), who toured the country for a few weeks in February to assess the outbreak and response efforts.

Does COVID-19 cause a lost sense of smell? [New, 3/23/2020]

There are some anecdotal reports that many people who have COVID-19 or go on to test positive for the disease experience temporary loss of their sense of smell and have a diminished sense of taste.

Data on this is lacking. In a press conference March 23, the WHO said it had likewise heard of these reports and is looking over data to confirm whether this is a common symptom of COVID-19.

However, epidemiologist Maria Van Kerkhove, an outbreak expert at the WHO, emphasized in the briefing that regardless of whether loss of the sense of smell is common, we already know the primary symptoms of the disease and the severe forms: fever, cough, fatigue, and shortness of breath.

How severe is the infection?

Most people infected will have a mild illness and recover completely in two weeks.

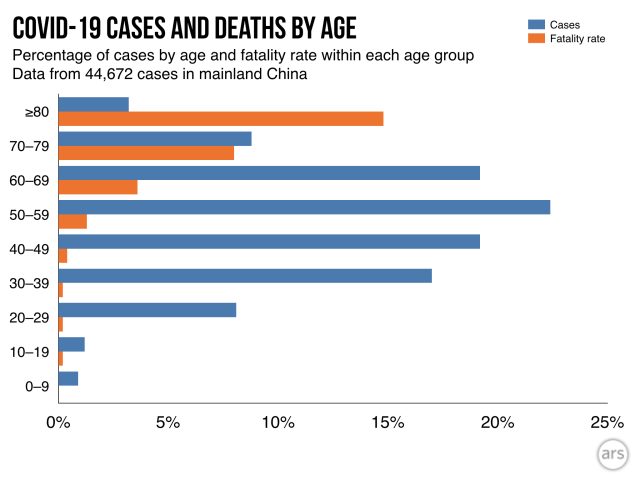

In an epidemiological study of 44,672 confirmed cases in China, authored by an emergency response team of epidemiologists and published by the Chinese CDC, researchers reported that about 81 percent of cases were considered mild. The researchers defined mild cases as those ranging from the slightest symptoms to mild pneumonia. None of the mild cases were fatal; all recovered.

Otherwise, about 14 percent were considered severe, which was defined as cases with difficult or labored breathing, an increased rate of breathing, and decreased blood oxygen levels. None of the severe cases were fatal; all recovered.

Nearly 5 percent of cases were considered critical. These cases included respiratory failure, septic shock, and/or multiple organ dysfunction or failure. About half of these patients died.

Finally, 257 cases (0.6 percent) lacked severity data.

The overall fatality rate in the patients examined was 2.3 percent.

Who is most at risk of getting critically ill and dying?

Your risk of becoming severely ill and dying increases with age and underlying health conditions.

In the group of 44,672 cases discussed above, the highest fatality rates were among those aged 60 and above. People aged 60 to 69 had a fatality rate of 3.6 percent. The 70 to 79 age group had a fatality rate of about 8 percent, and those 80 or older had a fatality rate of nearly 15 percent.

Additionally, the researchers had information about other health conditions for 20,812 of the 44,672 patients. Of those with additional medical information available, 15,536 said they had no underlying health conditions. The fatality rate among that group was 0.9 percent.

The fatality rates were much higher among the remaining 5,279 patients who reported some underlying health conditions. Those who reported cardiovascular disease had a fatality rate of 10.5 percent. For patients with diabetes, the fatality rate was 7.3 percent. Patients with chronic respiratory disease had a rate of 6.3 percent. Patients with high blood pressure had a fatality rate of 6.0 percent and cancer patients had a rate of 5.6 percent.

Puzzlingly, men had a higher fatality rate than women. In the study, 2.8 percent of adult male patients died compared with a 1.7 percent fatality rate among female patients.

Are men more at risk?

In multiple studies, researchers have noted higher case numbers in men than in women. The WHO Joint Mission report found that men made up 51 percent of cases. Another study of 1,099 patients found that men made up 58 percent of cases.

So far, it is unclear if these numbers are real or if they would even out if researchers looked at larger numbers of cases. It’s also unclear if this bias may reflect differences in exposure rates, underlying health conditions, or smoking rates that may make men more susceptible.

That said, sex differences have been seen in illnesses caused by SARS-CoV-2’s relatives, SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV. There is some preliminary research looking into this in mice. Some findings suggest that there may be a protective effect from the activity of the female hormone estrogen. Other research has also suggested that genes found on the X chromosome that are involved in modulating immune responses to viruses may also serve to better protect genetically female people, who have two X chromosomes, compared with genetic males, who have only one X chromosome.

Are children less at risk? [Updated 3/20/2020]

Yes, it appears so. In all of the studies and data so far, children make up tiny fractions of the cases and have very few reported deaths. In the 44,672 cases examined by the Chinese CDC, less than one percent were in children ages 0 to 9 years old. None of those cases was fatal. Similar findings have been reported in other studies.

The WHO-China Joint Mission report also noted that children appear largely unscathed in this epidemic, writing, “disease in children appears to be relatively rare and mild.” From the data so far, they report that “infected children have largely been identified through contact tracing in households of adults.”

An unpublished, un-peer-reviewed study of 391 cases in Shenzhen, China, seems to support that observation. It noted that within households, children appeared just as likely to get infected as adults, but they had milder cases. The study was posted March 4 on a medical preprint server.

Still, as the Joint Mission report noted, given the data available, it is not possible to determine the extent of infection among children and what role that plays in driving the spread of disease and the epidemic overall. “Of note,” the report went on, “people interviewed by the Joint Mission Team could not recall episodes in which transmission occurred from a child to an adult.”

UPDATE 3/20/2020:

With new data on cases in children trickling in, little has changed. Children still appear to be at lower risk of COVID-19. Though they can certainly become infected, they tend to make up small fractions of known cases in places. When they are infected, they tend to have mild illness and rarely develop severe disease. To date, there are few reports of children dying of COVID-19. The first was a 14-year-old boy in China’s Hubei province, who died on February 7.

A study came out in the journal Pediatrics this week that examines 2,143 cases of COVID-19 in children in China. The study is the first to offer a detailed look at so many cases, which are often hard to find.

Overall, it echoes what we already knew. “Clinical manifestations of children’s COVID-19 cases were less severe than those of adults’ patients,” the authors concluded. About 94 percent of the cases were mild or moderate.

But, like any demographic, children weren’t universally spared from severe outcomes. About 6 percent of cases were severe (about 5 percent) or critical (under 1 percent). And, perhaps most concerning, most of the severe and critical cases were in the youngest age groups, that is under-1-year-olds and 1- to 5-year-olds.

Those two groups accounted for 60 percent of severe cases (about 30 percent each) and nearly 70 of critical cases (54 percent in the under 1-year-olds).

While those figures are alarming, it’s important to note some of the limitations of this data. First, the numbers are small in the severe and critical categories. Percentages can be large just with a few cases. For instance, there were only 7 critical cases in children under 1 year old, but there were only 13 cases overall.

Also, not all of the cases in this study were confirmed COVID-19 cases. Some were suspected cases based on clinical findings. Of the 2,143 cases, 731 (34 percent) were laboratory-confirmed cases and 1412 (66 percent) were suspected. As such, other respiratory infections—that can be particularly severe for infants, such as RSV—can’t be ruled out.

Lastly, the researchers didn’t have any information on the overall health status of the children. It’s unclear if any underlying conditions contributed to the severity of disease.

Are pregnant women at high risk? [New, 3/19/2020]

The question of risks for pregnant women is, unfortunately, very difficult to answer right now. We simply don’t have much data.

So far, from the scant data we have, there’s little indication that pregnant women are at an increased risk of COVID-19. That is, pregnant women do not appear to have more severe disease than the rest of the population. And there have been no reported deaths of pregnant women due to COVID-19 at this time.

However, pregnant women are at increased risk of getting severely ill or dying from other respiratory infections, such as flu and SARS (which is caused by SARS-CoV, a coronavirus related to SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19). As such, The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) currently (as of 3/19) recommends that pregnant women be considered an at-risk population.

The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and other health agencies stress that pregnant women should strictly follow the same hygiene measures and social distancing recommended to prevent contracting the virus.

If a pregnant woman does contract the virus, here’s what we know so far:

For pregnant women:

You’ll most likely have mild to moderate symptoms, like the rest of the population. However, severe symptoms—particularly if you have underlying health conditions—can occur and should be promptly identified and treated.

In a non-peer-reviewed, unpublished study of 34 pregnant women with COVID-19 (16 laboratory confirmed and 18 suspected cases), none of the women developed severe disease. While the women had a higher rate of maternal complications than a control group, all of the complications developed prior to their COVID-19 cases. Those complications included gestational diabetes, premature rupture of membranes, and preeclampsia.

There is a report of a pregnant woman developing severe disease. She was admitted to the hospital at 34 weeks and had an emergency C-section of a stillborn baby before being transferred to the ICU with multiple organ dysfunction and acute respiratory distress syndrome.

For the fetus:

There is no evidence of increased risk of miscarriage or early-pregnancy loss.

There are reports of preterm birth, but it is so far unclear if those early births were due to COVID-19 in the mother.

There is no evidence that the virus infects in utero. In one small study, samples of amniotic fluid, cord blood, neonatal throat swab, and breastmilk from six pregnant women with laboratory-confirmed cases of COVID-19 were all negative for SARS-CoV-2. In another study, three placentas from pregnant women with COVID-19 also tested negative. And in other studies, newborns from symptomatic mothers tested negative for the virus.

There have been a few reports of newborn babies testing positive for the virus, but when they were infected remains unclear. It is possible that they were infected just after birth.

Expert opinion is that there is no intrauterine fetal infection. As such, it is considered unlikely that COVID-19 in a mother would lead to congenital effects from SARS-CoV-2 on the fetus.

US data on risk for millennials [New, 3/20/2020]

In a press briefing March 18, Dr. Deborah Birx, coordinator for the White House's coronavirus task force, tried to send a warning to millennials—people in their 20s and 30s—that they are not immune from getting severely ill with COVID-19. She noted concerning reports of young people getting seriously ill in France and Italy, potentially because they are not taking the pandemic risk seriously and getting infected disproportionally. (Here is some recent data on infections in Italy)

“We think part of this may be that people heeded the early data coming out of China and coming out of South Korea that the elderly or those with preexisting medical conditions were at particular risk,” she said. “It may have been that the millennial generation... there may be a disproportional number of infections among that group. And so even if it’s a rare occurrence, it may be seen more frequently in that group and be evident now.”

Her main point was that millennials can indeed become very ill—though at a lower rate than older groups—and they should certainly follow recommended health measures and social distancing like older adults. However, it may have come across to some as saying that millennials in the United States are getting sicker than expected.

The same day as Dr. Birx made the comments, the CDC released preliminary data on severe outcomes of COVID-19 patients in the US. The data may offer some eye-opening insights, but it’s not very different from what we’ve seen elsewhere.

Overall, the data echoed what has been seen in other countries, particularly in China. Patchy data from 4,226 COVID-19 cases in the US suggested that people aged 65 or older were most at risk: they made up 31 percent of cases despite being around 15 percent of the population. They made up 45 percent of known hospitalizations, 53 percent of known ICU admissions, and 80 percent of deaths. The age group with the highest rate of severe outcomes was the 85 or older group.

The data the CDC was working with was very preliminary and incomplete though. For many of the cases, researchers didn’t have data on age, whether a case required hospitalization or intensive care or not, or even whether the patient died or not. The data also didn’t included information on whether patients had underlying health conditions, such as cardiovascular disease or diabetes, which also increases risks of severe illness and death.

Still, some were struck by the breakdowns of that patchy data. Of 2,449 cases with a known age, 29 percent fell into the 20-44 age group. Of 508 cases that were known to be hospitalized, 20 percent were aged 20-44. And of 121 patients known to need intensive care, 12 percent were 20-44.

Last, among 44 cases with known outcomes, nine (20 percent) were in people aged 20-64.

The CDC’s finding that 20 percent of people hospitalized with COVID-19 were aged 20-44 might seem high. In one unpublished, non-peer-reviewed study, UK researchers estimated that people aged 20 to 49 would make up just about 9 percent of people requiring hospitalization for COVID-19. The estimate was based on data from 3,665 COVID-19 cases in China.

However, a closer look at that data from China doesn’t tell an entirely different story from what we’ve heard so far in the US. Of the 3,665 Chinese cases, 1,170 were among people aged 20-49. Of those, 173 were severe, likely requiring hospitalization. That suggests that about 15 percent of patients aged 20-49 with COVID-19 went on to need hospitalization.

In the new report on US COVID-19 data, the CDC estimates that between 14 percent to 20 percent of patients aged 20-44 require hospitalization.

Of course, in different places with different demographics, disease transmission dynamics, health care quality, etc., these types of figures will fluctuate. For instance, in one study looking at 262 COVID-19 cases just in Beijing, researchers found that 20 percent of severe cases were in people between the ages of 13 and 44.

The bottom line is that people aged 65 or older and those with underlying health conditions are still, clearly, most at risk for developing severe illness and dying from COVID-19. But people in the younger age groups are certainly not immune to those outcomes.

WHO Director-General Dr. Tedros emphasized this message to millennials in a press briefing March 20. “You’re not invincible,” he said, adding that the virus could put young people in the hospital for weeks.

And, even if younger COVID-19 cases get by with mild illness, they still have the potential to pass on the infection to more vulnerable groups.

Everyone, no matter age or health status, needs to follow the hygiene and social-distancing recommendations. Everyone.

How long does COVID-19 last?

On average, it takes five to six days from the day you are infected with SARS-CoV-2 until you develop symptoms of COVID-19. This pre-symptomatic period—also known as "incubation"—can range from one to 14 days.

From there, those with mild disease tend to recover in about two weeks, while those with more severe cases can take three to six weeks to recover, according to WHO Director-General Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, who goes by Dr. Tedros.

⇒ How many people die from the infection? [UPDATED 4/4/2020]

This is a difficult question to answer. The bottom line is that we don’t really know.

Case fatality rates (CFR)—that is, the number of infected people who will die from the infection—are simply calculated by dividing the number of dead by the number of recovered plus dead. The CFRs you’ve probably seen so far have likely been a crude version of this: deaths divided by total cases.

One problem with these crude calculations is that the cases we’re counting aren’t all resolved. Some of the patients who are currently sick may later go on to die. In that situation, the patients' cases are counted, but their deaths are not (yet). This skews the current calculation to make the CFR look artificially low.

But a much larger concern is that we are undercounting the number of cases overall. Because most of the COVID-19 cases that we know about are mild, health experts suspect that many more infected people have not presented themselves to health care providers to be tested. They may have mistaken their COVID-19 case for a common cold or didn’t notice it at all. In areas hard hit by COVID-19, there may not have been enough testing capacity to detect all of the mild cases. If a large number of mild cases are being missed in the total case count, it could make the CFR look artificially high.

The best way to clear up this uncertainty is to wait until one of the local outbreaks is completely over and then to do blood tests on the general population to see how many people were infected. Those blood tests would look for antibodies that target SARS-CoV-2. (Antibodies are Y-shaped proteins that the immune system makes to help identify and attack pathogens and other unfriendly invaders.) The presence of antibodies against a specific germ in a person’s blood indicates that the person has been exposed to that germ, either through infection or immunization. Screening the general population for SARS-CoV-2 antibodies will give a clearer picture of how many people were actually infected—regardless of whether they were symptomatic or diagnosed while sick. That number can then be used to calculate an accurate CFR.

So far, some preliminary population screening for COVID-19 infections has been done in China, specifically in Guangdong province. Screening of 320,000 people who went to a fever clinic suggested that we may not be missing a vast number of mild cases. This in turn suggests that the CFRs we are calculating now are not wildly higher than they should be. However, experts still suspect that many mild cases are going unreported, and many still anticipate that the true CFR will be lower than what we are calculating now.

Beyond getting the basic number of cases and deaths right, CFRs are also tricky because they can vary by population, time, and place. We’ve already noted above that the CFR increases in patient populations based on age, gender, and underlying health. But as time goes on, healthcare providers will get collectively better at identifying and treating patients, thereby lowering the CFR.

Complicating these statistics further, the quality of healthcare differs from place to place. The CFR in a resource-poor hospital may be higher than that in a resource-rich hospital. Additionally, health systems overwhelmed in an outbreak may not be able to provide optimal care for every patient, artificially increasing the CFR in those places.

This seems to be what we’ve seen in China so far. In the WHO-China Joint Mission report, the experts noted that in Wuhan—where the outbreak began and where health systems have been crushed by the number of cases—the CFR was a whopping 5.8 percent. The rest of China at the time had a CFR of 0.7 percent.

As of March 5, there were about 13,000 cases and 400 deaths reported outside of China’s Hubei Province (where Wuhan is located). A crude calculation puts the CFR around 3 percent, but this calculation will likely drift throughout the outbreak. We will update the current crude CFR periodically.

UPDATE 4/4/2020

As of April 4, there were 290,606 cases and 7,826 deaths in the US. A crude estimate puts the CFR at about 2.7 percent. In Italy and Spain, which have had devastating outbreaks, crude estimates of the CFRs are 12 percent and 9 percent, respectively.

How does COVID-19 compare with seasonal flu in terms of symptoms and deaths?

Most cases of COVID-19 are mild and may feel similar to the seasonal flu before a person recovers.

Though the case fatality rate is not yet clear for COVID-19 (as noted above), it so far appears to be significantly higher than the CFRs seen from seasonal flu in the US.

Overall CFRs for COVID-19 have hovered around 2 percent to 3 percent during the outbreak. As reported by Kaiser Health News, Christopher Mores, a global health professor at George Washington University, calculated the average 10-year mortality rate for flu in the US at 0.1 percent, based on CDC data. Many experts use this figure, including Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases at the National Institutes of Health.

Likewise, WHO Director-General Dr. Tedros noted in a recent statement that “seasonal flu generally kills far fewer than one percent of those infected.”

Still, a lower CFR doesn’t mean a low death toll. So far this flu season, the CDC estimates that up to 45 million Americans have been infected, hospitalizing up to 560,000 and killing 46,000.

Influenza remains a leading cause of death in the US.

How does SARS-CoV-2 spread? [Updated 3/12/2020]

SARS-CoV-2 spreads mainly in respiratory droplets—tiny, germ-toting globs that are launched from the mouth or nose when you breathe heavily, talk, cough, or sneeze. Published data suggests that a single sneeze can unleash 40,000 droplets between 0.5–12 micrometers in diameter. Once airborne, these fall rapidly onto the ground and typically don’t land more than one meter away.

If any droplets containing SARS-CoV-2 land on a nearby person and gain access to the eyes, nose, or mouth—or are delivered there by a germy hand—that person can get infected.

If droplets containing SARS-CoV-2 land on surfaces, they can get picked up by others who can then contract the infection. According to epidemiologist Maria Van Kerkhove, an outbreak expert at the WHO, SARS-CoV-2 appears to be like its relative, SARS-CoV, in that surface contamination does seem to play a role in the epidemic.

It is unclear how long SARS-CoV-2 can survive on any given surface. A recent review published in The Journal of Hospital Infection suggested that human-infecting coronaviruses in general may be able to survive on surfaces for up to nine days. A new non-peer-reviewed, unpublished study led by researchers at the US National Institutes of Health suggests that SARS-CoV-2 can last for hours to up to three days on surfaces, lasting longest on plastic and steel surfaces. The study was posted on a medical pre-print server March 10.

Likewise, the WHO says SARS-CoV-2 may survive on surfaces for anywhere from a few hours to several days. The organization also notes that survival will depend on environmental factors, such as temperature, humidity, and the type of surface.

SARS-CoV-2 is not thought to be transmitted in air, according to available data. However, the pre-print study by NIH researchers suggests that it may survive in aerosols for up to three hours.

Regardless of where it is, as Dr. Van Kerkhove noted, SARS-CoV-2 is quickly killed by disinfecting agents. As the review of coronavirus surface survival reported, the viruses are “efficiently inactivated by surface disinfection procedures with 62–71 percent ethanol, 0.5 percent hydrogen peroxide, or 0.1 percent sodium hypochlorite (bleach) within 1 minute.”

Last, genetic material from SARS-CoV-2 does seem to be shed in some patients' feces—potentially in up to 30 percent of patients, according to the report by the WHO-China Joint Mission. A recent study in JAMA also found the virus lurking in toilet bowl and bathroom sink samples. “However,” as the Joint Mission report states, “the fecal-oral route does not appear to be a driver of COVID-19 transmission.” Moreover, routine bathroom cleaning efficiently eliminated the infectious threat, the authors of the JAMA article concluded.

⇒ How does coronavirus transmission compare with flu? [UPDATE 3/13/2020, 4/4/2020]

In a press briefing on March 3, WHO Director-General Dr. Tedros emphasized that “this virus is not SARS, it’s not MERS, and it’s not influenza. It is a unique virus with unique characteristics.”

“Both COVID-19 and influenza cause respiratory disease and spread the same way, via small droplets of fluid from the nose and mouth of someone who is sick,” he said. “However… COVID-19 does not transmit as efficiently as influenza, from the data we have so far. With influenza, people who are infected but not yet sick are major drivers of transmission, which does not appear to be the case for COVID-19.”

While media reports have widely circulated fears that asymptomatic people are silently spreading COVID-19 around communities and countries, there is little data to back that up. In fact, asymptomatic cases appear rare and potentially misclassified. Dr. Tedros noted that only 1 percent of cases in China are reported as “asymptomatic.” And of that 1 percent, 75 percent do go on to develop symptoms.

Though it is still unclear to what extent infected people may spread the virus before developing symptoms, the WHO still reports that, based on the current data, the biggest drivers of COVID-19 spread are symptomatic people coughing and sneezing.

Moreover, the thrust of the epidemic in China has been from the spread of the virus through households and close contacts, not unconnected community members.

UPDATE 4/4/2020

As the pandemic has spread far beyond China, there has been a much greater focus on the issue of asymptomatic and pre-symptomatic spread of disease. There are clear documented cases in which people who are not experiencing symptoms have likely passed on the infection. However, it is still very unclear to what extent this is occurring and what role it plays in the pandemic overall.

For one thing, it's unclear what proportion of infected people are truly asymptomatic, meaning they never have symptoms during the course of their infection. Data from China suggests asymptomatic cases make up much less than 1 percent of cases, while Italian data suggests 7.5 percent are asymptomatic. Dr. Robert Redfield, director of the US CDC, has said up to 25 percent of cases could be asymptomatic.

Until blood tests can be done to assess the total number of people infected, it's extremely difficult if not impossible to determine what proportion of infected people have asymptomatic cases.

It also unclear how infectious people are if they have an asymptomatic case or if they are infected but have yet to develop symptoms. Some preliminary data has suggested that viral shedding from the upper respiratory tract is high right at or slightly before the onset of symptoms. However, it's unclear how easily the virus can reach its next victim without being propelled from helpful symptoms like coughs and sneezes.

Numerous modeling efforts have attempted to estimate how much asymptomatic or pre-symptomatic transmission is occurring based on the timing of cases. But, with so many questions still lingering about how the virus spreads and infects, these models rely on a number of assumptions. As such they offer an extremely wide range of estimates for what percentage of infected people picked up the virus from a symptomless person. Some have estimated 12.6 percent while others have estimated 62 percent in some places.

At this time, the WHO maintains that the main driver of COVID-19 transmission is people coughing and sneezing, thus launching respiratory droplets containing SARS-CoV-2. They note that an analysis of 75,465 COVID-19 cases found no instances of people contracting the infection from virus lingering in the air.

How contagious is it? [New, 3/9/2020]

From current data, the basic reproduction number (R0 or R naught) for COVID-19 is estimated to be between 2 and 2.5. That is, on average, a single infected person will go on to infect about two other people within a susceptible population. (Because SARS-CoV-2 is new to humans, everyone is assumed to be susceptible.)

The R0 generally is meant to represent an average. In this case, that means some people may infect fewer than two people, while a small proportion may be so-called super spreaders, who shed the virus more efficiently and infect far more than two additional people.

A few words of caution about interpreting R0: first, as Ars has reported before, R0 is a complicated calculation, and it isn’t necessarily intrinsic to a pathogen. R0 also doesn’t indicate how dangerous a disease is or how far it will spread. Last, transmission is context- and time-specific.

So far in this outbreak, the WHO has reported that transmission of SARS-CoV-2 has primarily been between people who have had contact with each other, such as family members. Also, transmission early in a case of COVID-19 (that is, 24 to 48 hours prior to noticeable symptom onset) does not seem to be common. Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 tends to be seen later, when symptoms are apparent, according to the WHO.

That’s in contrast to infections such as seasonal flu, which often spreads among unrelated people in the community and often before symptoms are apparent.

Seasonal flu has an estimate R0 of around 1.3. The highly contagious measles has an often-cited R0 range of 12 to 18, but some calculations have put the number at nearly 60.

In terms of the biology of what’s going on during transmission, many details remain unknown. So far, it appears that SARS-CoV-2 gets into human cells by latching onto a receptor molecular on the outside of cells called human angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2). These receptors are on cells found primarily in the lower respiratory tract. This may explain why COVID-19 includes fewer upper-respiratory-tract infection symptoms, such as a runny nose, and why SARS-CoV-2 does not seem to spread as readily in the pre-symptomatic period, like influenza.

That said, a non-peer-reviewed, unpublished study from Germany involving 9 COVID-19 patients suggested that patients may have high levels of virus in their upper respiratory tracts in the first week or so after symptoms are present. The study was posted March 8 in a medical pre-print server.

Can I get SARS-CoV-2 from my pet? Can I give it to my pet? [New, 3/9/2020]

Reports from Hong Kong recently raised concern that pets could be victims—or potentially sources—of SARS-CoV-2 after testing on a dog owned by a COVID-19 patient returned a “weak positive” result.

Though members of the coronavirus family do infect animals, including dogs, experts at the WHO and the CDC say that there’s no evidence that pets are getting sick from SARS-CoV-2 or transmitting the virus to people.

“We don’t believe that this is a major driver of transmission,” WHO epidemiologist Maria Van Kerkhove said in a March 5 press briefing. The dog in Hong Kong is only one case, she noted, and this issue requires much more study to assess its significance.

That said, as a general precaution, the CDC does suggest that if you are sick with COVID-19, you should try to “restrict contact with pets and other animals... just like you would around other people” until more information about the virus and its spread are known.

The infected pup in Hong Kong is said to have no symptoms but has been placed under quarantine as a precaution.

If I get COVID-19, will I then be immune, or could I get re-infected? [Updated, 3/20/2020]

The immune responses to a SARS-CoV-2 infection are not well understood, so there’s no clear answer on long-term immunity at this time.

There have been reports—such as this one from Japan—of COVID-19 patients who have recovered from the disease only to test positive for the virus again later. However, experts are skeptical that these are truly cases of relapsed infections or reinfections.

The tests used to determine if someone is infected rely on detecting tiny fragments of genetic material from the virus. While this is a good indication that someone has been infected, it doesn’t necessarily indicate that an infection is active or the genetic material is from an intact, infectious viral particle. The tests may simply be picking up genetic remnants of a past infection.

UPDATE 3/20/2020

While the question of immunity remains an open one, some new data suggests that people do develop immunity. A non-peer-reviewed, unpublished study involving four rhesus macaques found that after an initial infection with SARS-CoV-2, the monkey developed an adapted, strong immune responses to the virus. After researchers attempted to re-infect two of the monkeys, neither developed disease.

The finding needs to be replicated. Even if it is reproducible, it’s still unclear how long that immunity might last. However, the finding does cast further doubt that people who have recovered from COVID-19 are quickly becoming re-infected or experiencing relapses.

How likely am I to get it in normal life?

Your risk of exposure depends on where you live and where you’ve recently traveled. In the US, the virus is spreading in certain communities but is not thought to be circulating widely, according to the CDC. Unless there have been a number of cases reported in your area, your risk is considered low.

That said, with more testing happening, more cases will appear daily. There are basic things you can do to protect yourself and prepare for cases in your area.

What can I do to prevent spread and protect myself?

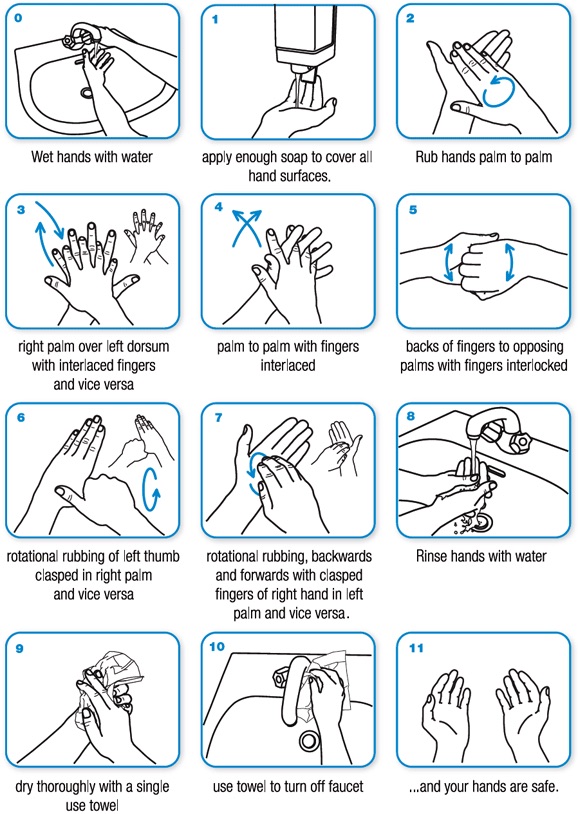

The most important things you can do to protect yourself from COVID-19 (as well as seasonal respiratory infections, like flu and cold) is to practice good, basic hygiene. That is:

- Wash your hands frequently and thoroughly.

- Make sure you wash your hands with soap and water for 20 seconds—the time it takes you to hum the Happy Birthday song twice. (One clever Twitter user came up with some alternative tunes for your mitt-scrubbing pleasure.)

- You should especially wash your hands before eating, after using the restroom, sneezing, coughing, or blowing your nose.

- If you can’t get to a sink, use a hand sanitizer that has at least 60 percent alcohol, the CDC says.

- Avoid touching your face, particularly your eyes, nose, and mouth.

- If you cough or sneeze, cover your face with your elbow or a tissue. If you use a tissue, throw that tissue away promptly, then go wash your hands.

- Avoid close contact with sick people. If you think someone has a respiratory infection, it’s safest to stay 2 meters away.

- If you are sick, try to stay home to get better and avoid spreading the infection.

- Regularly disinfect commonly touched surfaces and items in your house, such as door knobs and counter tops.

Should I get a flu vaccine?

YES. Getting a flu vaccine will protect you from the seasonal influenza and help prevent you from spreading that virus. Though the vaccine is not 100 percent effective, if you do still get sick with the flu after you are vaccinated, your illness will be milder than if you did not get vaccinated.

Getting a flu vaccine is something you should do every year to protect yourself and your community, including those most vulnerable to the infection and those who cannot get vaccinated for medical reasons. But, amid the COVID-19 epidemic, getting a flu shot is even more important.

COVID-19 can resemble the symptoms of influenza. If people are vaccinated against the flu and there are few cases of flu in an area, it may make spotting new COVID-19 cases easier. Moreover, healthcare systems around the country are already stretched thin by flu patients who need care and hospitalization each season. In this flu season so far, the CDC estimates that flu is responsible for up to 21 million medical visits and 560,000 hospitalizations.

Fewer flu patients means more healthcare resources can be directed to detect and treat COVID-19 cases and thwart the epidemic.

⇒ When, if ever, should I buy or use a face mask? [UPDATE, 4/4/2020]

If you are not sick, do not buy a medical face mask. If you have one already and you are well, it is not recommended that you use it.

Medical face masks (N95 respirators and surgical masks) are in short supply globally, and prices have surged. This is making it difficult for healthcare workers to get the supplies they need to keep themselves safe so they can stay healthy, keep treating patients, and avoid spreading the infection. This tragic situation is exacerbating the outbreak.

In a March 3 plea, the WHO called on industry and governments to step up production of masks and help thwart inappropriate buying.

“The World Health Organization has warned that severe and mounting disruption to the global supply of personal protective equipment (PPE)—caused by rising demand, panic buying, hoarding and misuse—is putting lives at risk from the new coronavirus and other infectious diseases,” the agency said in a statement.

“We can’t stop COVID-19 without protecting health workers first,” WHO Director-General Dr. Tedros said.

In addition to putting healthcare workers at risk, wearing a medical mask may also put you at risk. For one thing, face masks are not entirely effective. Masks still leave your eyes exposed—if rubbed with germy hands, they can be an entry point for viruses. Surgical masks are loose-fitting and leave open the possibility of infectious particles working their way around the mouth. Even the use of N95 respirators, which are designed to protect against respiratory droplets, may not be that helpful to you, since they require proper fitting, and many people do not wear them correctly or consistently.

Some experts suggest that when members of the public wear face masks, they tend to fuss with them and touch their faces more. This increases the risk of transferring pathogens from hands to entry points. Also, if you touch the outside surface of a contaminated face mask, you can then contaminate your hand and go on to infect yourself. This negates the purpose of wearing a face mask.

Last, some health experts worry that wearing face masks may give people a false sense of security, potentially making them lax about other precautions and protections.

The only time experts recommend that members of the public wear a medical mask is if they are caring for a sick person or are already sick and showing signs of COVID-19. In that case, wearing a mask could reduce the risk that you will spread the infection to others.

Otherwise, medical masks should be reserved for healthcare workers.

Update 4/4/2020

The US CDC and some health experts now recommend that seemingly healthy people should wear cloth masks/face coverings when out in public, particularly in areas where community-based spread of COVID-19 is occurring.

Though cloth masks are much less effective than medical masks at blocking viral transmission, the CDC and others believe that they may be useful in preventing or at least reducing the amount of viral spread from pre-symptomatic or asymptomatic people.

The CDC guidance does not change the need and recommendation to reserve medical masks for frontline healthcare workers. Cloth masks and face coverings can be made out of fabrics and items already in your home, such as old t-shirts, towels, and handkerchiefs.

The guidance also does not change the need to observe social distancing and hygiene measures.

Should I avoid large gatherings and travel? [Updated 3/13/2020]

Yes.

If you live in the US, experts say that now is the time for social distancing measures—that is, putting distance between you and other people as much as possible. Avoid gatherings, unnecessary outings, and any unnecessary travel. If you can work from home, do so. School systems are already starting to close in many places. If yours hasn’t yet, start making plans of what you’ll do if or when it does. If you need to go to the doctor, call ahead and ask about tele-health options.

If you must go out or travel, try to stay 2 meters (about 6 feet) away from people. Practice good hygiene: wash your hands with soap and water frequently, cough and sneeze into your elbow, avoid touching your face.

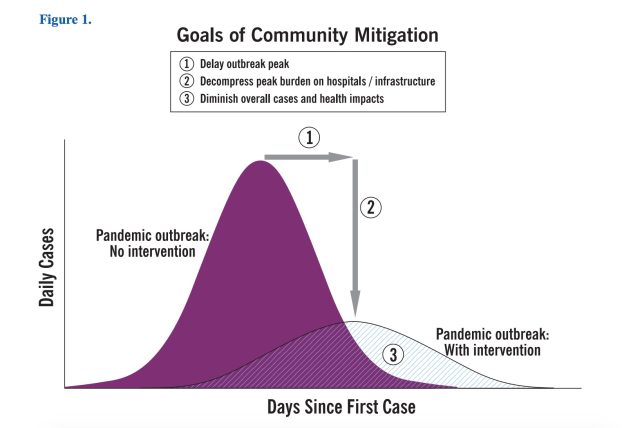

Social distancing “is not a panacea,” Dr. Michael Ryan, executive director of WHO’s Health Emergencies Program, cautioned in a press briefing March 13. This isn’t going to stop the epidemic, he explained, but it will slow it down and allow health systems to better cope with the burden of mounting COVID-19 cases.

Though most cases of COVID-19 are mild, many will require hospitalization. In a study of 44,672 cases in China, around 14 percent needed hospitalization. If a scenario close to this plays out in the US, every hospital bed in the US may be occupied by mid-May, according to some estimates.

Social distancing may help avoid or delay that. But ultimately the way to stop the epidemic is for officials to start widespread testing, identify cases, put infected people in isolation, trace their contacts, put them in quarantine, and continue monitoring.

So far, that has not been happening in the US. The country’s response has been severely crippled by extremely limited and slow testing. As a country, we are not doing enough testing to know how far SARS-CoV-2 has spread in communities now, let alone to prevent further spread.

The worst of the outbreak is yet to come for the US, Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the NIH’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, said in a Congressional hearing on Wednesday, March 11.

"I can say we will see more cases, and things will get worse than they are right now," Fauci said. "How much worse we'll get will depend on our ability to do two things: to contain the influx of people who are infected coming from the outside, and the ability to contain and mitigate within our own country."

For those who must travel internationally, the CDC provides risk assessments and travel guidance on its website here.

For people outside of the US, in areas where SARS-CoV-2 is not yet known to be circulating, the original response from 3/8/2020 is below:

Unfortunately, there is no clear or general answer to the question of travel and attending large gatherings. Like your risk of exposure generally, risk from attending events and traveling depend on where you are and where you are going.

Any time you’re faced with such a decision amid this epidemic, you should consider not only your local risk but also whether you will encounter people from high risk areas while traveling to the event or once you are at it.

For local events largely attended by local people in communities where there are no or limited cases, attending is considered low risk. Traveling to or through areas experiencing large clusters of cases will certainly increase your risk of contracting COVID-19. Attending a conference where there will be groups of people from high-risk areas also increases your risk.

But of course, these risk assessments only hold up if we have a firm grasp of where the virus is circulating. Right now, we’re not in a good place to assess this, according to Harvard epidemiology professor Marc Lipsitch.

“A month ago, it was easier to answer and, I think, a month from now it will be easier to answer,” Lipsitch said in a COVID-19 forum at Harvard on March 2. “Right now, it’s possibly the hardest time to answer.”

Earlier, the outbreak was mostly in China’s Hubei Province, so it was easy to recommend travel restrictions to and from there. And a month from now, the virus may be so widespread that traveling doesn’t change your risk much—or it could be contained and it will be clear which places are low or high risk (we can hope).

But for now, the virus is scattering around the globe. It’s hard to pin down which places are low and high risk. With new cases popping up continually, the situation in any given place can change at a dizzying pace.

For anyone facing criticism of being too cautious, Lipsitch did say that “limiting optional travel makes a lot of sense.” High risk or not, “it’s part of a response to try to slow this down.”

What precautions should I take if I do travel?

If you must travel, avoid contact with sick people, wash your hands frequently, use hand sanitizer, and avoid touching your face.

If you’re traveling by air, avoid layovers in high-risk areas.

Do quarantines, isolations, and social-distancing measures work to contain the virus? [New, 3/10/2020]

Yes, for the most part.

When the epidemic of COVID-19 first exploded out of Wuhan in January, officials in China and other countries began issuing quarantines, imposing social-distancing measures, and setting travel restrictions.

China locked down tens of millions of people in late January, for instance. In the Hubei province, where Wuhan is located, officials implemented so called “social distancing measures,” cancelling events and gatherings, closing schools, having people stay at home, and upping sanitation and hygiene measures. Meanwhile, other countries issued travel restriction. The United States, for instance, barred entry of some foreign nationals with recent travel to China.

Some public health experts were critical of the moves, calling some of them draconian and ineffective. For instance, quarantines, which can clumsily round up the sick with the healthy, may not prevent the spread of disease—which we certainly saw on the Diamond Princess cruise ship, quarantined in Japan. And travel restrictions in our highly-connected world are inevitably leaky.

But proponents of the policies were quick to argue that the measures were never intended to hermetically seal off cities or countries. Rather, the moves were intended to slow down the spread of disease. This can buy officials time to prepare, help avoid overwhelming healthcare facilities with a burst of cases, and in the end, lower the overall case counts in an epidemic.

According to the latest data, those proponents of the measures were, on the whole, correct.

In the WHO-China Joint Mission report, the group of experts estimated that China’s massive efforts to contain the virus have “averted or at least delayed hundreds of thousands of COVID-19 cases in the country.” This, in turn, had helped blunt the impact on the rest of the globe, they add.

Further, in a new non-peer-reviewed, unpublished study, an international team of researchers estimated that without the measures, the number of cases in mainland China would have been 67-times higher. And if officials had begun implementing them just one week earlier, cases could have been reduced by 66 percent. If they had implemented them three weeks earlier, cases would have been reduced by 95 percent. The study appeared on a medical pre-print server March 9.

Likewise, in another non-peer-reviewed, pre-print study, this one led by epidemiologists at Harvard, researchers estimate that early interventions—quarantines, social distancing, contact tracing, etc.—successfully and dramatically blunted the peak burden of disease in the Chinese city of Guangzhou.

In a Twitter thread March 10, one of the coauthors of that study, Harvard epidemiologist Marc Lipsitch, noted that as community spread increases, social distancing—however painful—becomes essential to slowing and minimizing the impact of disease.

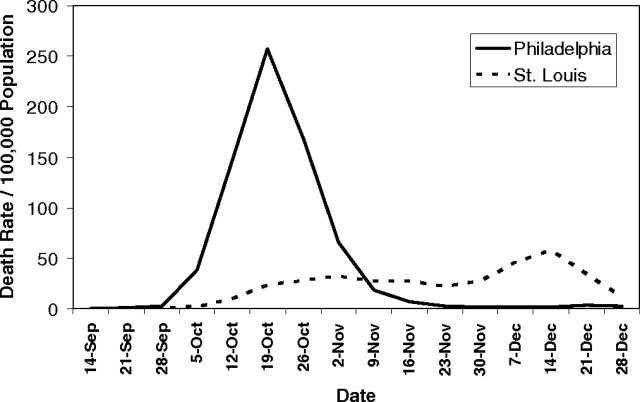

In the thread, he references a comparison of outbreaks of the 1918 pandemic flu in Philadelphia and St. Louis. In Philadelphia, authorities downplayed the spread of disease and did not issue social-distancing measures quickly. They even went forward with a city-wide parade as the disease spread. St. Louis, on the other hand, quickly implemented social distancing measures within days of the area’s first reported cases. The graph below shows how well things worked out for each city.

How should I prepare for the worst-case scenario?

This epidemic is unpredictable, and it is possible that it could begin spreading in your community. That might lead to problems in the supply chain of various foods and goods—such as masks. It might also mean that local authorities will recommend “social distancing” measures, asking that you spend more time at home as events and gatherings get cancelled. Schools may close down for periods to try to stop disease spread. Employers may recommend working from home when possible, and healthcare providers may push the use of tele-health services.

In the event you get sick with COVID-19, you will likely face a two-week isolation period at home, unless your illness becomes severe and you require medical care at a hospital.

Experts suggest that if you haven’t already, go ahead and start putting together an emergency stash of food and supplies for these scenarios, but do not panic buy and do not hoard. Just pick up a few extra items on your routine shopping trips that will help make sure you don’t run out of food if you’re stuck in your house for two weeks. Stick with shelf-stable items that you’ll use regardless of how this epidemic plays out—things like dried pasta, canned foods, beans, lentils, peanut butter, trail mix, nuts, shelf-stable or powdered milk, coffee, cereal, cooking oil, and other grains.

Since it’s unlikely that we will lose power or municipal water, it’s probably safe to stock up on some frozen items you normally eat—and you can skip buying a lot of bottled water.

In addition to food, you should think about having some extra supplies of home goods and medicines on hand. If you take prescription medications, try to have extra doses (though this can be difficult to do).

Keep your home comfortably stocked with things like toilet paper, tissues, diapers, soap, cleaning products and sanitizers, pet foods, and feminine products. Again, don’t hoard. Just buy a bit extra in case you need to skip a routine shopping trip or two.

If things look like they’re going to get really bad in terms of supply-chain issues, you can dash out in the eleventh hour to pick up whatever dairy, produce, meat, or baked goods you can get.

The CDC has a detailed list of other items to keep on hand in general emergencies.

Should I keep anything in my medicine cabinet for COVID-19? [Updated, 3/16/2020]

With most mild to moderate cases involving nonspecific, flu-like symptoms, you may want to make sure you have enough fever-reducer/pain reliever, such as ibuprofen or acetaminophen (see the update below).

You might also want to consider keeping over-the-counter treatments for colds around, just because it’s that season. Upper respiratory symptoms like productive coughs and nasal congestion were not common symptoms of COVID-19, but they are sometimes present.

Otherwise, there aren’t specific treatments.

Update: A note about ibuprofen as well as ACE inhibitors, angiotensin II type-I receptor blockers (ARBs), and other anti-inflammatory drugs that may be used to treat diabetes and cardiovascular disease:

There have been hypotheses and speculation that these drugs could increase people’s risk of being infected with SARS-CoV-2 or make COVID-19 cases more severe. Some researchers have hypothesized that this may be the case because these drugs could increase a person’s amount of ACE2 receptors. These are molecules on the outside of some human cells that SARS-CoV-2 can latch onto, allowing the virus to get into those cells and replicate.

Some officials have even suggested that COVID-19 patients avoid taking ibuprofen for fever and pain and stick with acetaminophen (Tylenol).

So far, there is not sufficient evidence to support the hypothesis or the clinical recommendation. Some medical experts, including the European Society of Cardiology, have even made a point to release statements urging patients to continue taking their prescription medications.

Some experts have noted that favoring acetaminophen to treat COVID-19, out of an abundance of caution, isn’t a terrible idea. But people should follow dosages carefully since the drug can be toxic to the liver.

We'll update this section as more information is available.

Can X home remedy or product prevent, treat, or cure COVID-19? [New, 3/11/2020]

A word of caution about misinformation and fraudulent claims.

Like any pressing health topic, there will be plenty of people attempting to exploit the situation for personal gain, whether it be money or status (particularly on social media). The Internet is rife with false information about SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19 as well as bogus products and strategies to combat them. This will likely intensify as the pandemic escalates in the United States.As the FDA noted in an enforcement action this week: there are currently no vaccines or drugs approved to treat or prevent COVID-19.

“Although there are investigational COVID-19 vaccines and treatments under development, these investigational products are in the early stages of product development and have not yet been fully tested for safety or effectiveness,” the agency says.

So, no, eating lots of garlic and huffing essential oils won’t ward off COVID-19. Spraying colloidal silver up your nose won’t stop SARS-CoV-2 from invading. Getting vaccines that protect against other pathogens—such as the influenza virus or bacteria that cause pneumonia, such as Streptococcus pneumoniae (pneumococcus)—are also not going to prevent COVID-19. (For more examples, the WHO has a site dedicated to myth busting.)

These fraudulent claims waste money, give people a false sense of security, delay actual medical care and treatments, and can sometimes be outright dangerous.

Should I go to a doctor if I think I have COVID-19?

If you believe you have COVID-19, the CDC advises you should call your healthcare provider—do not make an unannounced office visit. Your healthcare provider, with the help of your state’s health department and the CDC, can determine if you should come in and get tested. Obvious reasons to test include the presence of COVID-19-like symptoms, having had contact with someone known to be infected, living in a place where transmission is occurring, or if you have recently traveled to a place where transmission is occurring.

If you do have COVID-19, getting tested can help local health departments track the virus’ spread and identify contacts who may have also been exposed. Once your case is confirmed, your healthcare provider and local health department can work with you to monitor and manage your health and assess when you’re no longer at risk of spreading the infection.

But it’s important that you call ahead before going to a healthcare provider if you’re concerned you have COVID-19. This will help determine if you can and should be tested and provide your healthcare provider with a chance to prepare the office so you will not potentially expose people in the facility or patients in the waiting room to the virus.

If a healthcare provider has you come in for a test, the CDC recommends wearing a mask and, as always, practicing good hygiene.

When should I seek emergency care?

If you have a confirmed case of COVID-19 or if you have a suspected case and your condition worsens and you have trouble breathing, call your doctor immediately to seek prompt medical care.

If your condition becomes an emergency, call 911 and inform them that you may have COVID-19. Wear a mask if possible when emergency responders arrive.

Is the US healthcare system ready for this?

As experts at the WHO have repeatedly warned, COVID-19 can put enormous strain on healthcare systems. For weeks, they have been advising for countries to get ready and have a plan.

So far, there have been worrying signs that the US healthcare system has not heeded this warning. Last week, news broke of a whistleblower allegation that the Department of Health and Human Services sent dozens of untrained employees without protective gear to help manage repatriated citizens at high risk of COVID-19 and under quarantine.

On March 5, The New York Times reported that nurses in Washington and California—where SARS-CoV-2 is circulating in some communities—have had to beg for masks and have been pulled from quarantines to treat patients.

In a survey of more than 6,500 nurses in 48 states by National Nurses United, a nationwide union of nurses, only 29 percent reported that their hospitals had plans in place to isolate possible COVID-19 cases. Only 44 percent said their employer had provided them with guidance on how to respond to potential COVID-19 cases, and only 63 percent said they had access to N95 respirators.

There have also been anecdotal reports from Washington and California of people trying to get tested for the virus but being told that there were no tests available.

What are the problems with testing in the US?

Testing for COVID-19 in the US has been a tragic debacle.

The CDC was tasked with coming up with a diagnostic test to detect SARS-CoV-2 in respiratory samples from patients. The agency developed an RT-PCR test for the new virus and sent testing kits beginning in early February to states. But, as the agency notes on its website, “shortly thereafter performance issues were identified related to a problem in the manufacturing of one of the reagents which led to laboratories not being able to verify the test performance.”

While the CDC has been mum about what exactly went wrong, a report in Science suggests that the problem was with a negative control in the kit—a sample designed to produce a negative test result. Should that control return a positive result, it would render test results uninterpretable, since there's no way of knowing if positive results are actually due to the presence of the virus. A report in Axios suggests that the problem may have been due to contamination.

The problem took the agency weeks to resolve, and many states weren’t able to ramp up testing until the end of February and start of March. “This has not gone as smoothly as we would have liked,” Dr. Nancy Messonnier, director of the CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, said in a press briefing February 28.

The testing snag cost the country precious time in detecting imported cases, isolating them, and tracing their contacts—critical steps needed to contain the virus.

In March, things began improving. The CDC has worked out the problem with its tests, the FDA has loosened regulations on who can design their own tests, and commercial tests are coming online to provide additional kits to states.

Unsurprisingly, in the first few days of increased testing capacity, the number of confirmed cases in the US exploded.

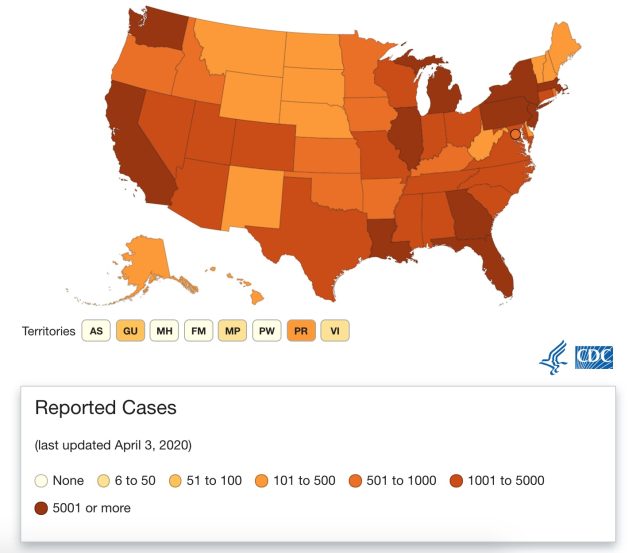

⇒ Current cases in the US [Updated, 4/4/2020]

As of April 4 at 3pm ET, the US has now detected far more cases of COVID-19 than any other country in the world, including China. At this time, there are nearly 300,000 cases confirmed nationwide and more than 8,000 deaths. With testing for COVID-19 in the United States severely delayed and still limited, the number of actual cases is expected to be much higher.

All 50 states, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, Guam, and the US Virgin Islands are reporting cases. West Virginia, the last state to detect cases, announced its first case on Tuesday, March 17.

Here is the latest map from the CDC from April 3 showing affected states, with a color gradient indicating case ranges in each state. Note that the CDC data sometimes lags behind some case reporting by state and local health departments. This map is sometimes missing cases, but you can get a general idea of the country’s situations. Generally, for a more up-to-date reference, you can check out the global COVID-19 dashboard, put together by researchers at Johns Hopkins University.

Among the hardest hit states are New York, New Jersey, Michigan, and California.

Washington state is currently reporting 6,976 cases and 295 deaths. Washington was the first state to report a case in the whole of the United States back in January. A Seattle-area man in his 30s developed symptoms after returning from a trip to the area around Wuhan, China, where the outbreak began. The current outbreak in the state may link back to that initial case, according to preliminary genetic analyses.

New York and New Jersey are now the epicenter of the country's outbreak. New York is reporting 113,806 cases and 3,565 deaths. Of the cases, 63,306 are in New York City.

On March 14, New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio announced the state’s first death in an elderly woman with advanced emphysema. “We all have a part to play here,” he said in the announcement. “I ask every New Yorker to do their part and take the necessary precautionary measures to protect the people most at risk.”

In a press briefing, March 24, after the case count had mushroomed, New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo warned the country: “We are your future."

Nearby New Jersey is reporting 34,124 cases with 846 deaths.

California is reporting 10,701 cases and 237 deaths. The state has housed hundreds of quarantined citizens repatriated from China and passengers from two coronavirus-stricken cruise ships.

What could happen if healthcare facilities become overwhelmed?

If the situation in the US or in certain communities gets out of hand—and it’s not at all clear if this will happen—hospitals and healthcare facilities may not be able to handle the number of COVID-19 patients seeking care. This could lead to suboptimal care for those patients, potentially increasing the case fatality rate in the country.

If healthcare systems are overwhelmed, the severe and critical cases will likely get priority, potentially allowing mild cases to go undetected and untreated. This could in turn allow the virus to keep spreading.

Again, it is unclear if this will happen. It is a worst-case scenario that can, in part, be avoided if individuals do their part to stop the spread of the disease with hygiene recommendations and mitigation efforts such as social distancing.

When will all of this be over in the US?

No one knows. Such epidemics are extremely unpredictable, but experts expect that COVID-19 will be with us for at least the coming weeks and months.

Will SARS-CoV-2 die down in the summer?

So far, we have no evidence that SARS-CoV-2 will be stifled by warming temperatures, WHO epidemiologist Maria Van Kerkhove says.

It’s unclear exactly why influenza and other respiratory viruses tend to peak in colder months. Some evidence suggests that the lower temperatures and lower humidity may help viruses spread. But we don't know if that's true for this coronavirus.

Will it become a seasonal infection?

This is also unknown, but some epidemiologists—including Harvard’s Marc Lipsitch—suggest that SARS-CoV-2 could be with us indefinitely and that we will eventually see it return in seasonal waves.

What about treatments and vaccines?

Since the epidemic began in January, researchers have rushed to start clinical trials and begun developing vaccine candidates. There are now dozens of vaccine efforts underway.

The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases at the National Institutes of Health has partnered with biotechnology company Moderna to test a vaccine candidate based on messenger RNA that will cause an individual's cells to produce a viral protein without an infection. An early clinical trial in people is expected to start in the coming weeks. If it is successful, a usable vaccine will still take at least a year and a half, according to NIAD’s director, Dr. Fauci—and that is a very optimistic estimate.

Meanwhile, researchers and biotech companies are also working on treatments for COVID-19.

On February 25, the NIH announced that a clinical trial has begun to test whether an experimental antiviral drug called remdesivir can help COVID-19 patients hospitalized in Nebraska Medical Center (UNMC) in Omaha.

Researchers are also working on plasma-derived treatments, which have some positive anecdotal reports. The basic idea behind plasma therapy is to harvest antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 from the blood plasma of infected patients after they’ve recovered. Those collected antibodies can then be injected into newly infected patients, where they could bolster immune responses, potentially improving outcomes and shortening recovery times. On March 4, Takeda Pharmaceutical Company announced that it is beginning work on a plasma-derived therapy for COVID-19.

A list of all updates and additions

March 9, 3pm ET: Added three new question-and-answer sections and updated case counts.

March 10, 3pm ET: Added one new question-and-answer section and updated case counts.

March 11, 3pm ET: Added a new section about claimed remedies and updated case counts.

March 12, 3pm ET: Updated the sections on US cases and how SARS-CoV-2 spreads. Updated global case counts.

March 13, 3pm ET: Updated the answers to "Should I avoid large gatherings and travel?" and "How does coronavirus transmission compare with flu?" Also updated global and US case counts.

March 14, 3pm ET: Updated global and US case counts.

March 15, 3pm ET: Updated global and US case counts.

March 16, 3pm ET: Updated global and US case counts. Updated guide on what to keep in your medicine cabinet.

March 17, 3pm ET: Updated global and US case counts.

March 18, 3pm ET: Updated global and US case counts

March 19, 3pm ET: Added new section on risks for pregnant women. Updated global and US case counts

March 20, 3pm ET: Added a new section on the risk to US millennials. Updated the section on risk to children and the section on reinfection. Updated global and US case counts.

March 21, 3pm ET: Updated global and US case counts.

March 22, 3pm ET: Updated global and US case counts.

March 23, 3pm ET: Added section on loss of smell. Updated global and US case counts.

March 24, 3pm ET: Updated global and US case counts.

March 25, 3pm ET: Updated global and US case counts.

March 26, 3pm ET: Updated global and US case counts.

March 27, 3pm ET: Updated global and US case counts.

April 4, 3pm ET: Updated sections on deaths, how transmission compares with flu, and masks. Updated global and US case counts.

https://news.google.com/__i/rss/rd/articles/CBMia2h0dHBzOi8vYXJzdGVjaG5pY2EuY29tL3NjaWVuY2UvMjAyMC8wNC9kb250LXBhbmljLXRoZS1jb21wcmVoZW5zaXZlLWFycy10ZWNobmljYS1ndWlkZS10by10aGUtY29yb25hdmlydXMv0gFxaHR0cHM6Ly9hcnN0ZWNobmljYS5jb20vc2NpZW5jZS8yMDIwLzA0L2RvbnQtcGFuaWMtdGhlLWNvbXByZWhlbnNpdmUtYXJzLXRlY2huaWNhLWd1aWRlLXRvLXRoZS1jb3JvbmF2aXJ1cy8_YW1wPTE?oc=5

2020-04-04 19:35:00Z

52780706532073

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Don’t Panic: The comprehensive Ars Technica guide to the coronavirus [Updated 4/4] - Ars Technica"

Post a Comment